by Carrie Pomeroy

I’m reaching the end of my work day on a Tuesday when my phone buzzes.

“Going to Colin’s tonight?” my friend texts me. “I’ll be there around 5.”

“Yep,” I text back. “Me too.”

At 5pm, I walk over to Zion Lutheran Church (aka Zion Community Commons or ZCC) a red-brick building at the corner of Aldine and Lafond in St. Paul’s Hamline-Midway neighborhood. I’m not a member of the Zion congregation, not a churchgoer at all. What draws me here are the community meals and open markets hosted here three days a week, open to all comers. And even more than the food, what draws me is the camaraderie I find here.

I enter through a bright green side door facing Aldine. To the right of the door, a hand-lettered cardboard sign wedged into some propped wooden pallets says, “Warming House.” That handmade sign and the many colorful flyers for upcoming events taped to the door signal that this place is hopping—and just a little rough around the edges.

I head downstairs to the church kitchen and dining hall. There’s a line down the narrow hallway between the bathrooms and the kitchen. People standing in line wave and greet each other with smiles. Booming laughter and loud conversation ring out from the kitchen, where volunteers are helping Colin Anderson, a co-founder of the Twin Cities Vegan Chef Collective, to prep and serve tonight’s meal. I can smell the mouth-watering scent of whatever is being served that night, beckoning me in.

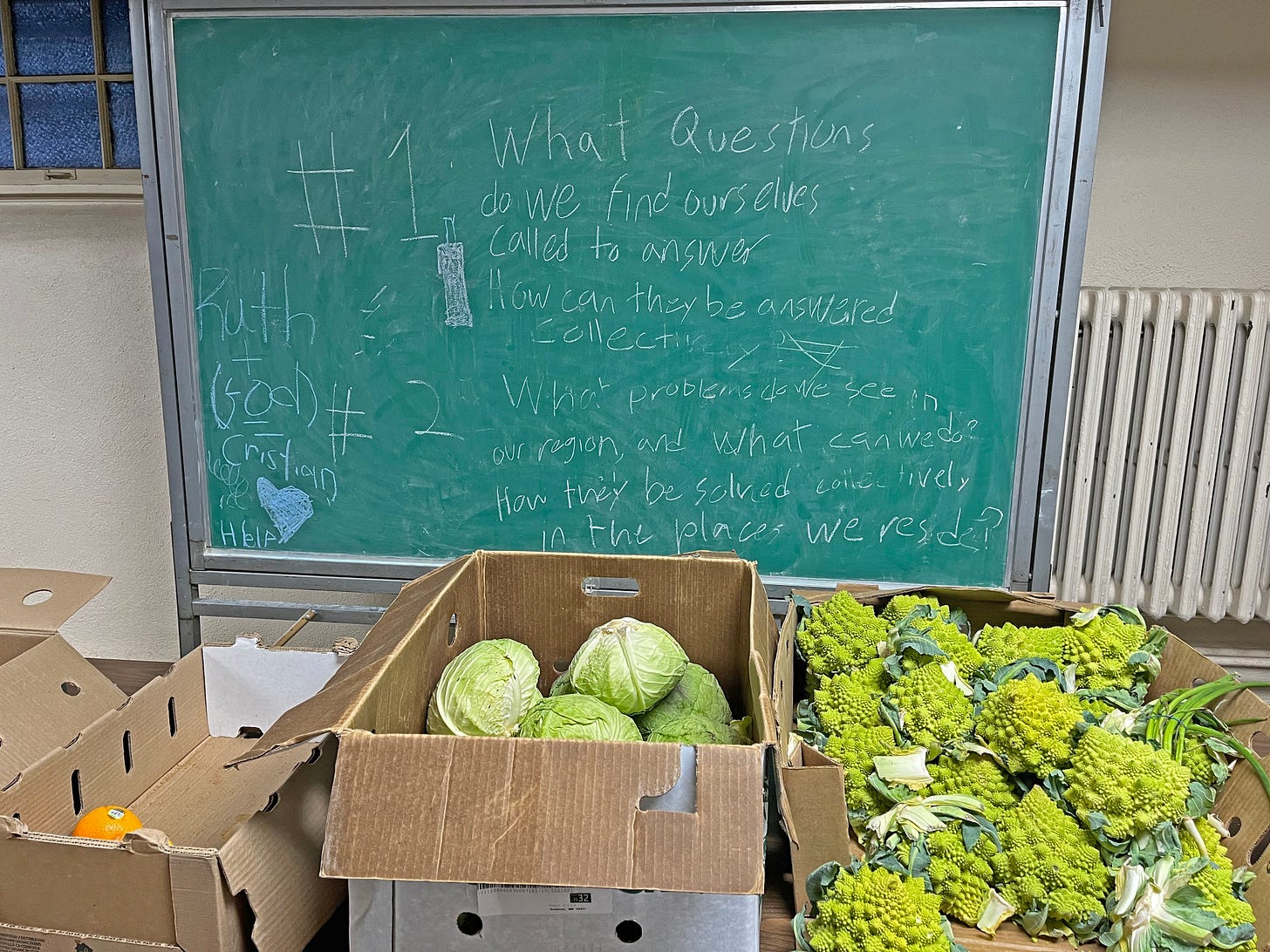

Inside the dining area, I read the day’s menu scrawled on a green chalkboard. Tonight, it’s rice and edamame jumble, crispy lemony beets, garlic black beans and roasted salsa, red vinegar kale, and apple spice scones. Sounds like it’s going to be a good night for my taste buds. One thing I’ve learned from coming to the meals at Zion is that if I like the food that night, I’d better savor it, because I’m never going to see the same meal on the menu twice. Colin and the other ZCC chefs cook with what they have on hand, prioritizing local, sustainable ingredients and meals that are free of common allergens, and they don’t like to repeat themselves. Every meal is a moment, a snapshot in time.

I see some of my friends already sitting at a table and go get some hugs. Then I head to the kitchen window. Colin booms out a hearty “Hey hey!” and hands me a full plate.

I use the Vegan Chef Collective’s CashApp handle to send them some money, but even if I didn’t send them anything, I would still be welcome to eat. At these meals, no one is turned away for lack of ability to pay. There’s a jar by the window where folks can drop cash if they’re able, with a scrap of paper taped to the jar with the Twin Cities Vegan Chef Collective’s Venmo and Cash app handles. Those of us who can pay help fund the meals for everyone. About 300 people also contribute regularly via the Vegan Chef Collective’s Patreon account.

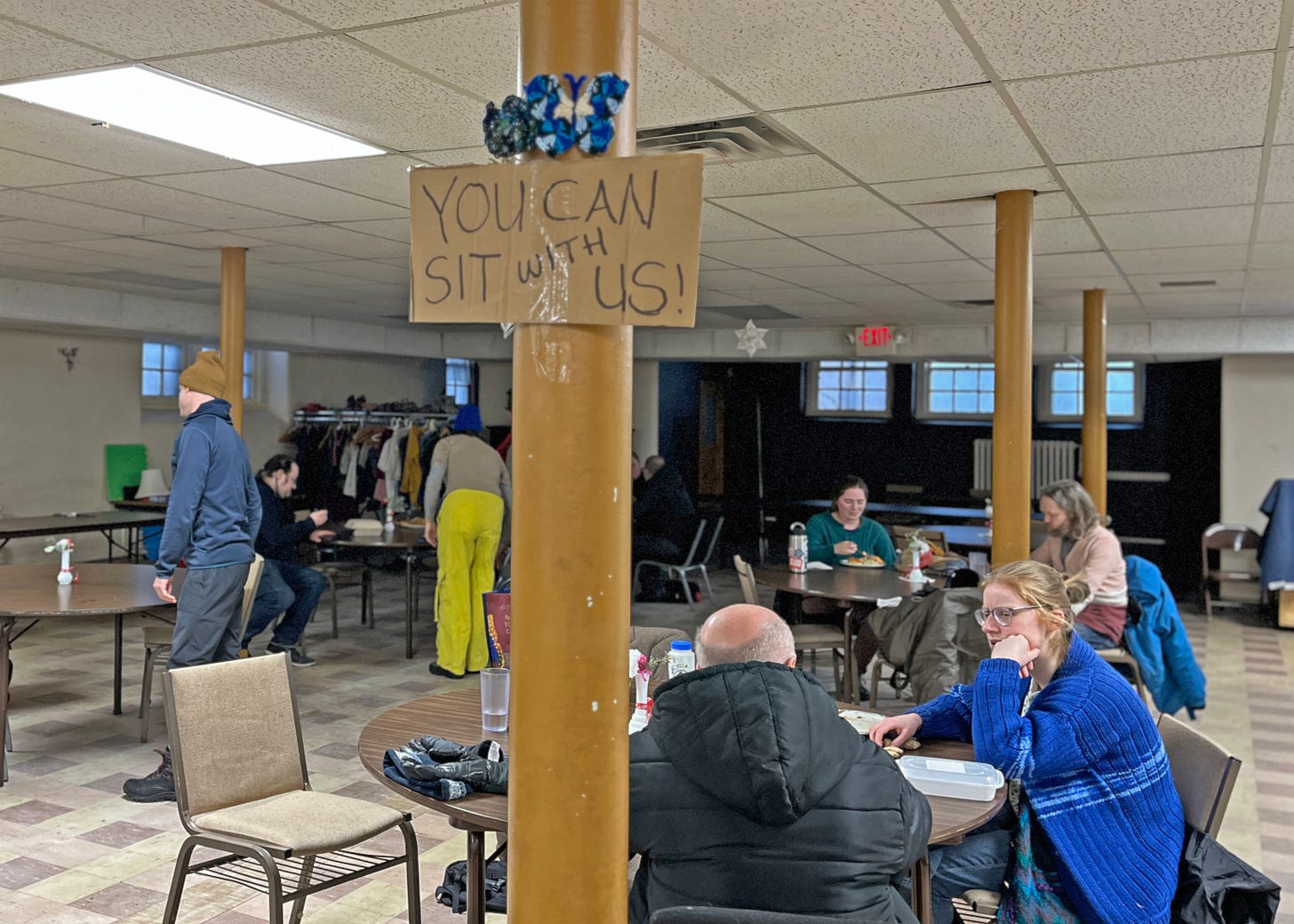

Walking to my table with my plate, I see another handwritten cardboard sign, this one taped to a support post. The sign says, “You can sit with us.” How many of us have had the experience as a kid of walking into a school cafeteria clutching our lunch tray, wondering if anyone will let us sit with them? Probably most of us. In the basement at Zion Community Commons, there is always someone you can sit with.

Food justice in action

We’re living in times that can often feel like an Octavia Butler dystopia come to life. These days, I’m finding solace and inspiration in local spaces where I can gather with my neighbors and friends.

At Zion Community Commons, the Twin Cities Vegan Chef Collective, a dedicated group of volunteers, and nonprofit partner Prevail News are working, with the support and blessing of church pastor John Marboe, to offer their pay-what-you-want, pay-what-you-can meals almost every Tuesday and Thursday. Zion Lutheran Church has hosted meals and free grocery giveaways on Thursdays for fifteen years, but in the last couple of years, the Vegan Chef Collective has expanded those offerings and put their own radical spin on food justice and community-building. They host not only the meals but also offer generous open markets, where you can stock up on fresh produce and staples like dried beans, oats, flour, sugar, tofu, and more.

Spaces like the community meals and open markets fill a pressing need in St. Paul. Currently, about one in 10 Ramsey County adults and one in five children are food insecure, with some of the highest rates of hunger in my own backyard in the Hamline-Midway neighborhood, Frogtown, and Capitol Heights.

Due to systemic, historically entrenched inequities, children, elders, and Black and brown people disproportionately experience chronic hunger. Almost 30 percent of Black Minnesotan households are food insecure compared to only 7 percent of white households. For children, hunger can make it harder to concentrate and succeed in an educational system that many young people experience as disempowering, hostile, coercive, and alienating—especially disabled youth, queer and trans youth, and youth of color. These injustices will only get worse as Trump’s administration demolishes federal programs to fund tax cuts for the super-wealthy.

When I fill my bag at the open market, no one ever monitors how much I take, and I would never even think to monitor anyone else; we trust each other to take just enough and not be greedy.

In addition to the community meals and markets, Colin and a team of volunteers have regularly packed up meals, sometimes up to 100 meals a week, for street outreach to unhoused people and local encampments of houseless people. Colin has applied some community donations to purchasing and distributing warm weather gear and tents, as well. Local musicians Mira and Tom Kehoe also offer an eclectic mix of arts programming at Zion Community Commons, everything from experimental jazz to sound baths to a Balkan guitar duo. A community meals patron named Bethany Mae has organized a community open mic talent show at ZCC and currently offers both a weekly space where people can talk about whatever they’re reading and a monthly salon aimed at promoting and nurturing creativity.

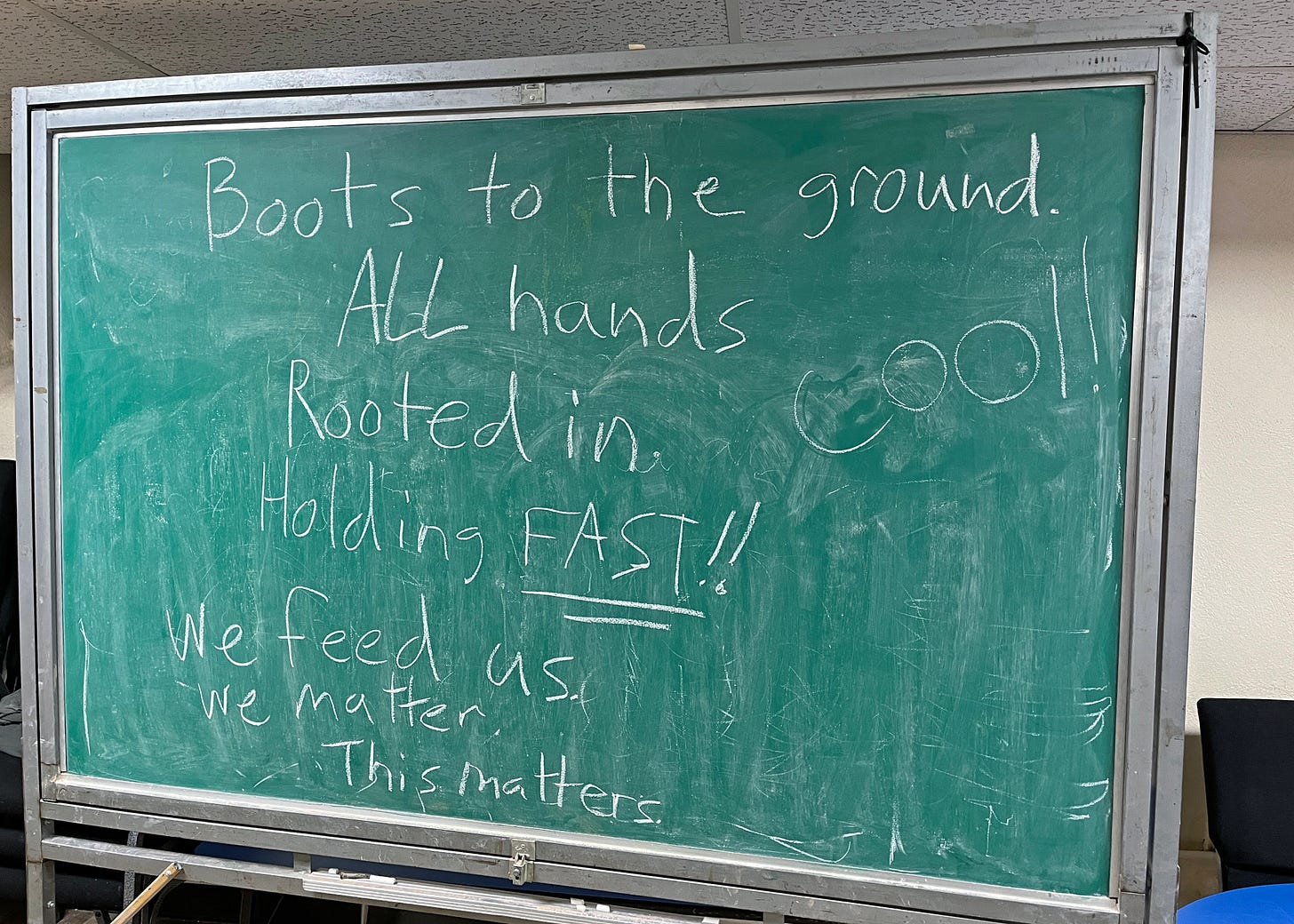

Who’s going to feed us? We’re going to feed us.

A break doesn’t always mean an ending

As the Appalachia-based trans writer, podcaster, and community organizer Margaret Killjoy put it in an April 2023 Instagram post, as we face the cruelty, greed, and uncertainty of living through late-stage capitalism, a pandemic that is still very much with us, and climate emergency, it’s time to “deescalate all conflict that isn’t with the enemy.” In a more recent interview with journalist and organizer Kelly Hayes, Killjoy expanded on that idea, saying, “We are really good at finding what’s wrong with each other. We really need to challenge ourselves to be ready to let people be better.” I resonate with that a lot, and I also know these are really challenging, complex principles to put into practice.

Colin is a neighbor of mine, and I’ve known him for about fifteen years. I first met him when my kids and I heard banjo music drifting from his open garage while we were out for a walk and we wandered into his alley to investigate. Colin was rehearsing with Loud Ray, the folk-punk string band he was in at the time. He and I continued to say hi to each other as we crossed paths in the neighborhood.

A few years later, Colin opened Eureka Compass Vegan Foods, a vegan bodega and bakery, in a building across from Zion Lutheran Church. During the COVID pandemic and the uprising after George Floyd’s murder, Colin and Eureka Compass were a lifeline in the neighborhood. He provided contact-free grocery pick-up at a time when many stores were boarded up and many people were afraid to go far from home or risk catching COVID to shop. Colin provided many thousands of dollars worth of food mutual aid during those tumultuous months. I will never forget the way he showed up.

Colin has strong opinions and he isn’t one bit shy about voicing those opinions. He will tell you in no uncertain terms, why, although he’s a dedicated vegan, he still thinks it’s more ethical for people to eat eggs from backyard hens than it is to eat cashews shipped to the U.S. from the Amazon. With little to no prompting, he will tell you exactly why beer production is unconscionable because it fuels alcohol addiction and uses inordinate amounts of water. Around 2019-2020, Colin liked to harangue me when I came into his store about how Bernie Sanders supporters were hypocrites…when I had a Bernie Sanders sign in my front yard. I didn’t always love getting an earful when I just wanted to pick up a bag of tortilla chips and be on my way, but I thought Colin was doing amazing things, and I appreciated that he was so very real and passionate about what he believed, so I tried to take his comments in stride. I could have tried getting into more of a conversation with him about why he felt the way he did about Bernie Sanders supporters (or about some of the many other hot-button issues he regularly brought up around the store), but I wasn’t sure there was much point in getting into it. He had his views; I had mine.

There came a time when I had an interaction with Colin that irked me enough that I decided that I needed a break. It’s not all that important why I decided that; it wasn’t anything all that serious. I still sent money every month to the Vegan Chef Collective through their Patreon, though not that much, really, considering how much I appreciated their work. But I didn’t attend the meals that Colin started to host at local churches after he made the decision to close his bodega. I viewed what he was up to in the neighborhood from a distance.

Then, in the last year or so, a dear friend of mine started going to the meals at the ZCC. Their non-profit job doesn’t pay them nearly enough, food prices are super-high, and they appreciated the way the open markets and meals helped them stretch their food dollar. They invited me to join them, but for a long time, I said no.

A few months ago, though, I decided to give the meals a shot, mainly because it was an easy way to hang out with my friend. Maybe I was a little lonely. I’d separated from my husband and moved into an apartment of my own. My young adult kids had both moved out.

I didn’t know if it would be awkward after staying away for so long. But when I showed up at the community meal, Colin greeted me with open arms and his usual booming gusto, as if it hadn’t been years since I’d come to one of his meals. As if no time had passed at all.

At this point, I’ve lived long enough in this neighborhood that there are people I once got along with great, people I was close to, that I now might cross the street to avoid if I saw them coming. Hell, they may feel the same way about me. I think this is not an uncommon phenomenon when you live in a neighborhood for 25 years and actually give a damn. You are going to butt heads with other people sometimes. You’re going to have differences of opinion on tactics or priorities. I haven’t talked to some of these folks in so long, I have no way of knowing if they’d avoid me if they saw me. Maybe they wouldn’t mind talking again, sharing a meal.

I used to feel a lot of shame about the tensions I feel with some of my neighbors and my lack of courage when it comes to talking things through with them. But sometimes it just isn’t the right time to talk. Sometimes a conversation is necessary; sometimes maybe it isn’t. Sometimes maybe you just show up again for each other, sidle up alongside each other and do what you can together to make your neighborhood better. When it comes to community, finding comfort and solace together doesn’t always mean staying absolutely comfortable; it doesn’t mean a complete absence of tension or irritation. Sometimes you do have to cut ties, set a boundary, draw a line. But a break doesn’t always mean an ending.

You just have to show up

These days, the community meals and open markets are a place I can go if I’m feeling tired at the end of my workday. I know I’ll be fed. I won’t be alone.

Almost always, I run into someone I know at the community meals. One day, I ran into a woman that I was in a drumming class with over a decade ago and had only seen on Facebook since. Another day, I recognized a person who had volunteered at an event with the organization I work for. Informal social gathering spaces like this, that bring people together who might not normally eat together, help us all share resources. They help us strengthen our collective ability to survive when prices keep rising, rents are too high, and jobs are hard to come by.

Last week, an elderly woman I’d never met before joined me and my good friend, the one who inspired me to attend the community meals. After my friend had to take off, the older woman and I got into a deep, vulnerable conversation about the challenges of aging, how the pandemic had changed us, and the ways we worried about the young people in our lives. These sorts of encounters knit our community together in ways that online interaction simply can’t touch. They might just save someone’s life.

The meals provide me and my friends an easy way to get together without having to plan ahead of time, too, a kind of crossing-paths-at-the-village-well convenience—a huge gift when we spend so much of our working lives scheduling meetings, and our ability to build relationships is constrained by the time slots available on our calendars.

We also don’t have to worry about cleaning up our own houses or apartments in order to access companionship—to do the kind of work that disproportionately falls to women. Like many women, I’ve logged decades of unpaid and underpaid work taking care of others. It feels like a luxurious gift to have Colin hand me a loaded plate and then, after I’ve eaten my fill, to drop off my empty plate for him or a volunteer to wash for me. Their care for me strengthens my ability to support my friends, family, co-workers, and community.

At the federal level, our government is trying to violently force us to be in a heterosexual marriage or nuclear family in order to receive this kind of care and security. In a February 19 Substack post, “Make America Isolated Again,” Iowa writer Lyz Lenz, author of the 2024 book This American Ex-Wife, points out that Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy’s recent order announcing that the DOT will be prioritizing issuing grants, loans, and contracts to places with higher-than-average marriage and birth rates “helps set in motion a vision of American life that is small, isolated, and alone.”

As Lenz puts it, in the America that Trump and his Project 2025 handlers envision, “There is no room for versions of family or community outside one man, one woman, and a handful of children.”

What Colin and the volunteers and chefs he works with are offering is an antidote to this narrow, limited vision. At ZCC, you don’t have to be in a traditional heterosexual marriage or conventional family to deserve and receive companionship, welcome, and security. You just have to show up.

A vulnerable future

Last fall, Zion Community Commons’ food justice programs won a federal grant designed to connect local growers and food producers with food-insecure people. The grant enabled ZCC to purchase high-quality local food through the nonprofit The Good Acre and expand the generosity and abundance of the open markets.

But only a few months into the program, on February 7, 2025, came bad news: thanks to Trump and Elon Musk’s anti-democratic coup, the promised grant funding has been frozen, leaving the church in the lurch for purchases already made in expectation of reimbursement—and throwing the future of the program into doubt. Many community members responded by increasing the amount of our Patreon monthly donation, or becoming paid members for the first time, or sending one-time contributions.

For now, Colin and his collaborators aim to continue offering this space. There are a lot of people determined to support that goal. For my part, I’ve tried to dig a little deeper and increase my financial commitments to the meals. It can feel risky, overcoming my own scarcity mentality to give more money to something that might disappear tomorrow. But I think this is exactly the kind of risk and discomfort that real community requires of us.

Real community also requires us to let go of the control we have when we interact primarily online, where we can scroll away if someone annoys us, or block out certain kinds of people, depending on the filters we’ve set on a dating app. I think it was valid for me to take a break from the community meals when I needed to—sometimes we all need to set some boundaries and take time to assess and regroup—but I’m so glad that I overcame my reasons for staying away and walked through the green door at Zion Community Commons. I have a long way to go when it comes to being able to talk through disagreements and annoyances instead of running away; I think a whole lot of us do, and we’re going to need to exercise those conflict resolution muscles more and more to be able to hold each other through the times we’re in.

No matter what, I want to keep finding ways to walk into that church basement, week after week. I want to see that cardboard “You can sit with us” sign, and know that there’s a place in my neighborhood where anyone can come in and take a seat and feel, even if it’s just for a half-hour or so, that in that place, in that moment, they are absolutely, unquestionably welcome.

Zion Community Commons offers free or pay-what-you-want, pay-what-you-can meals and groceries at 1697 Lafond Avenue in St. Paul on most Tuesdays, 11 a.m.-8 p.m., and Thursdays, 1-3 p.m. and 5-8 p.m. All are welcome.

To donate to the Twin Cities Vegan Chef Collective’s mutual aid and food justice initiatives, you can send money via CashApp to $ChefCollective1123 or via Venmo at @Chef-Collective-1123. For updates on the meal and market schedule and menus, follow Twin Cities Vegan Chef Collective on Instagram and/or follow and support them on Patreon. To receive updates about arts and community-building programming at Zion Community Commons, follow Bethany Mae on Instagram and Arts on Lafond on Facebook.

Such a wonderful story about the ZCC and TCVCC. So real!

beautiful! This is real. i'm there regularly. Thank you for telling it like it is!!